| KEY POINTS - CLINICAL PRESENTATION AND DIAGNOSIS |

|---|

| Genital warts are visible lesions that vary widely in appearance and distribution in the anogenital area, and there is good correlation between physical findings and histological studies. |

| Diagnosis is generally made by direct visual inspection with bright light, and potentially using magnification. |

| Differential diagnosis of genital warts requires exclusion of other anatomical findings such as vestibular papillomatosis, pearly penile papules, seborrheic keratoses, dermatoses, and intraepithelial neoplasia. |

| Genital warts that have an atypical appearance should be biopsied to exclude alternate diagnoses, especially intraepithelial neoplasia. |

| The use of HPV DNA testing for the diagnosis of anogenital warts is not recommended because test results do not confirm the diagnosis and do not facilitate management. |

| KEY POINTS - TREATMENT |

|---|

| The primary goal of treatment is to eliminate warts that cause physical or psychological symptoms. Non-treatment is an option for asymptomatic warts and the cure should not be worse than the disease. |

| There is no definitive evidence that any one treatment is superior to others, and no single treatment is suitable for all individuals or all warts.(1) |

| Methodological difficulties in designing randomised controlled trials and the frequency of spontaneous regression means that there is limited evidence to inform best practice for the treatment of genital warts. |

| The method of treatment should be determined by individual preference, available resources and healthcare professional experience. Other relevant factors include the size, number and site of the warts, the age of the individual being treated, and whether they are pregnant. |

| Individuals should be given information about all treatment options (including no treatment) to allow them to make an informed decision about their preferred approach. |

| No treatment is a realistic option given that about 30% of individuals will experience spontaneous clearance of warts over a 6-month period. However, many people will seek treatment to remove the discomfort, anxiety, social stigma and fears about transmission. |

| There is no specific treatment for subclinical HPV infections, most of which resolve spontaneously.(2) |

| People with a small number of low-volume warts, irrespective of type, can be treated with either ablative therapy or topical treatment. Podophyllotoxin for 4 weeks or imiquimod for 16 weeks are suitable at-home treatments in this setting. Individuals should be shown how to find lesions, apply treatment, and manage any treatment-related discomfort and local skin reactions. |

| Soft, non-keratinised warts respond well to cryotherapy, imiquimod or podophyllotoxin. Dry, keratinised warts may be better treated with ablative methods such as cryotherapy, excision or electrocautery. Aggressive ablative therapy should be avoided over the clitoris, glans penis, urinary meatus, and the prepuce in uncircumcised men. Ablative treatment, especially to the introitus, can result in disabling chronic pain syndrome or hyperaesthesia at the treatment site. |

| Because all available treatments have limitations, some clinics use combination therapy (e.g. provider-administered cryotherapy with individual-applied topical therapy between provider visits). However, there are limited data about the efficacy or risk of complications associated with combination therapy. |

| All treatments have significant failure and relapse rates. |

| If there is no significant response to treatment within 4–6 weeks after therapy initiation, an alternative diagnosis, change of treatment modality, or onward referral should be considered. |

| Although genital warts can disappear after treatment, the underlying viral infection may or may not persist. |

| The elimination of external visible warts may not decrease infectivity; warts may not represent the entire viral burden because internal sites and clinically normal skin may act as reservoirs for HPV infection. |

Diagnosis

Variants of genital warts

There are four variants of genital warts(3):

- Skin-coloured filiform warts (condyloma acuminata) occur on moist mucosal skin.

- Skin-coloured raised papules with a rough warty surface (verruca vulgaris) arise on drier areas of genital skin.

- Smooth flat-topped pink, red, brown or black papules (carpet warts) can develop on either dry or moist skin.

- Giant condyloma up to 4 cm in size with a cauliflower surface and red or pink in colour usually arise on dry genital skin.

Genital warts are often multifocal (one or more lesions at one anatomic site, e.g. vulva), or multicentric (lesions on disparate anatomic sites, e.g. perineum and cervix).(4-6) Lesions can also occur on the vagina, cervix, urethral meatus and anal canal. It is important to examine the entire lower genital tract for the presence of multicentric visible warts before treatment.

Perianal lesions are common in both males and females, including heterosexual men. These are not exclusively associated with anal sex due to the regional spread of HPV infection. However, they are more common in men who have sex with men.

Differential diagnosis

Most warts are clinically recognisable (see Dermnet NZ for pictures). However, some require examination under magnification (e.g. with a dermatoscope or colposcope) to distinguish from other lumps (e.g. vestibular papillomatosis or molluscum contagiosum). For many individuals, the psychological impact of warts is significant. If the diagnosis is uncertain, it is useful to get a second opinion (either from a colleague or a specialist).

There is no reliable way to determine whether sexual partners are infected with HPV or not. HPV DNA tests cannot be used for ‘routine’ screening because commercial assays are only used to detect high-risk HPV types and do not detect low-risk HPV or latent (i.e. undetectable) HPV. The application of 3–5% acetic acid (which might cause affected areas to turn white) is not a specific test for HPV infection and is not recommended.

The differential diagnosis of genital warts requires exclusion of any of the following:

- Normal anatomic variants in females, such as vestibular papillae, prominent sebaceous glands (Fordyce spots) and skin tags (acrochordans).

- Normal anatomic variants in males, such as sebaceous glands (Tyson’s glands), pearly penile papules, skin tags, angiofibroma.

- Infections such as molluscum contagiosum and condylomata lata (syphilis).

- Dermatoses and benign neoplasms, such as seborrhoeic keratoses, melanocytic naevus, angioma, lymphangioma, psoriasis and lichen planus.

- High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL; previously called vulval intrapepithelial neoplasia [VIN]).(7) HSIL usually presents as white, red or pigmented papules or plaques (which may be itchy, but can be asymptomatic). The lesions may have a warty surface and can be unifocal or multifocal. A lesion may be small and discrete or could be an extensive plaque covering most of the vulval or perianal skin. It may be clinically indistinguishable from the papular form of external genital warts, but appears more disorganised (see Dermnet NZ for pictures).(8, 9) Histological examination of these lesions shows high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia. HSIL is usually associated with HPV type 16 infection.

- Vulval cancer (this may arise from HSIL as a tumour or ulcer).

- There are a number of clinical variants of penile intraepithelial neoplasia, many of which are associated with HPV type 16 infection (see Dermnet NZ for pictures).(10)

- Penile and anal cancer; these usually present as a small nodule that may be ulcerated, and is most commonly found on the glans, coronal sulcus and prepuce. Untreated, the nodule will progress to a large ulcerated plaque.

Treatment

External genital warts

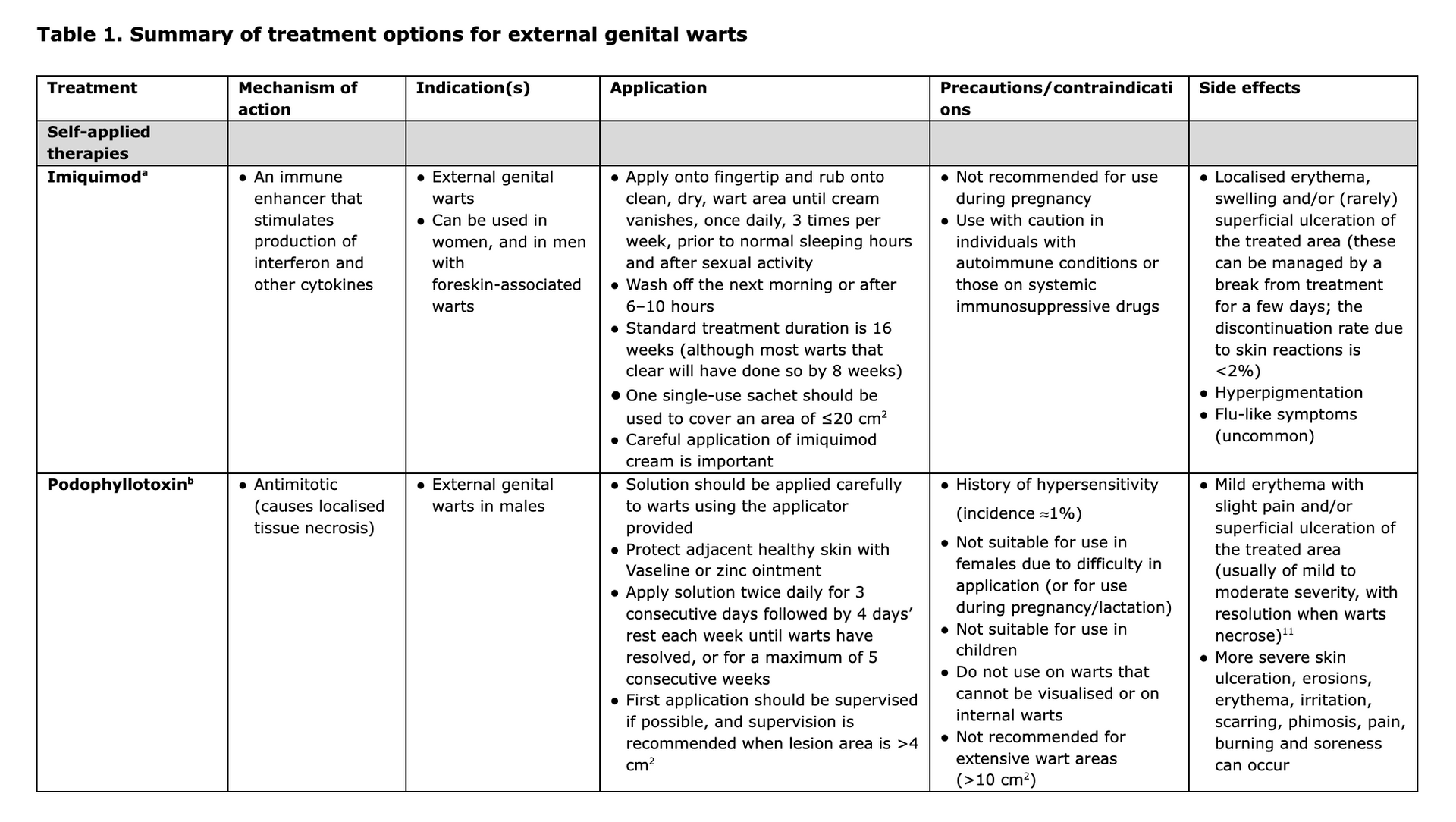

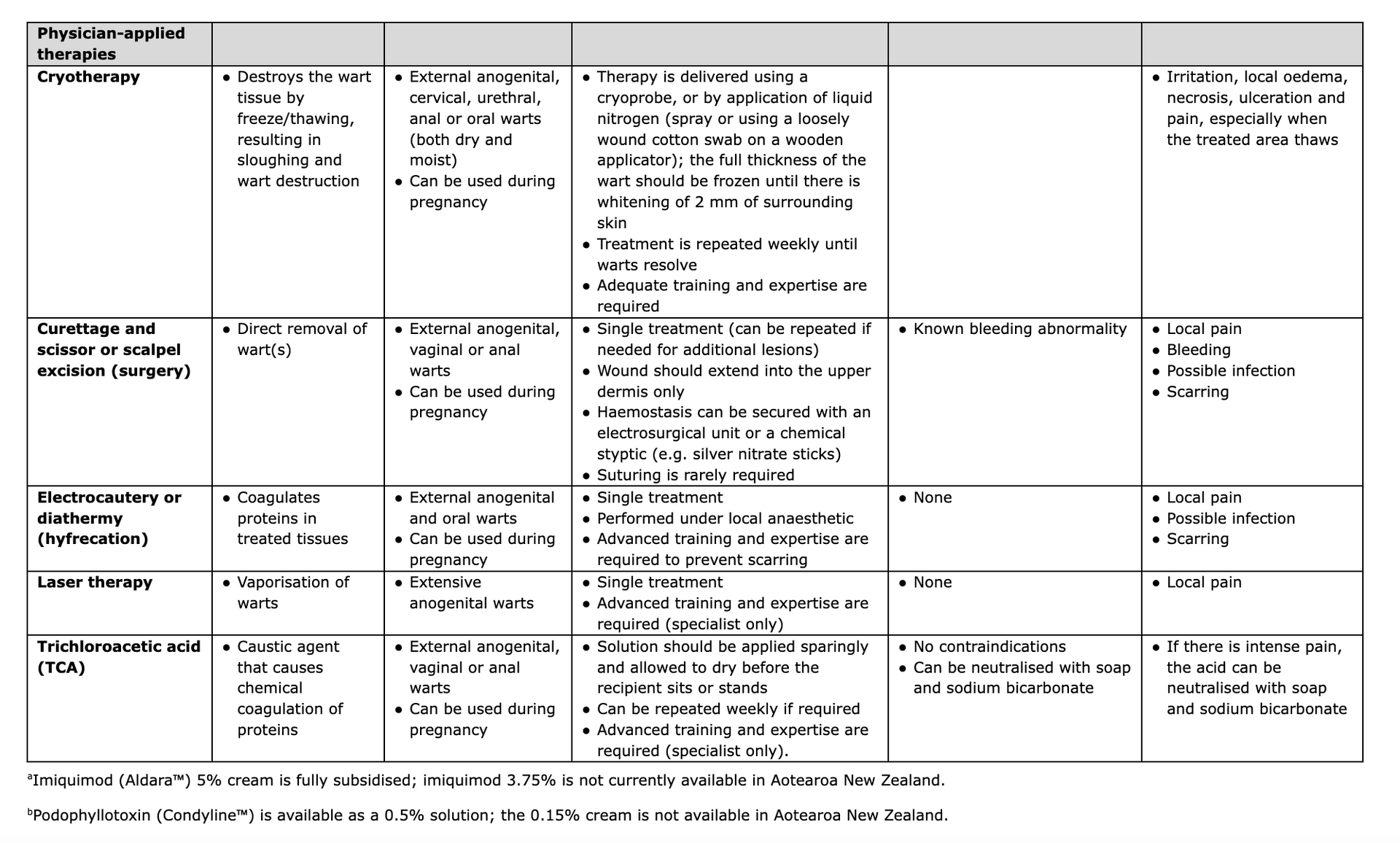

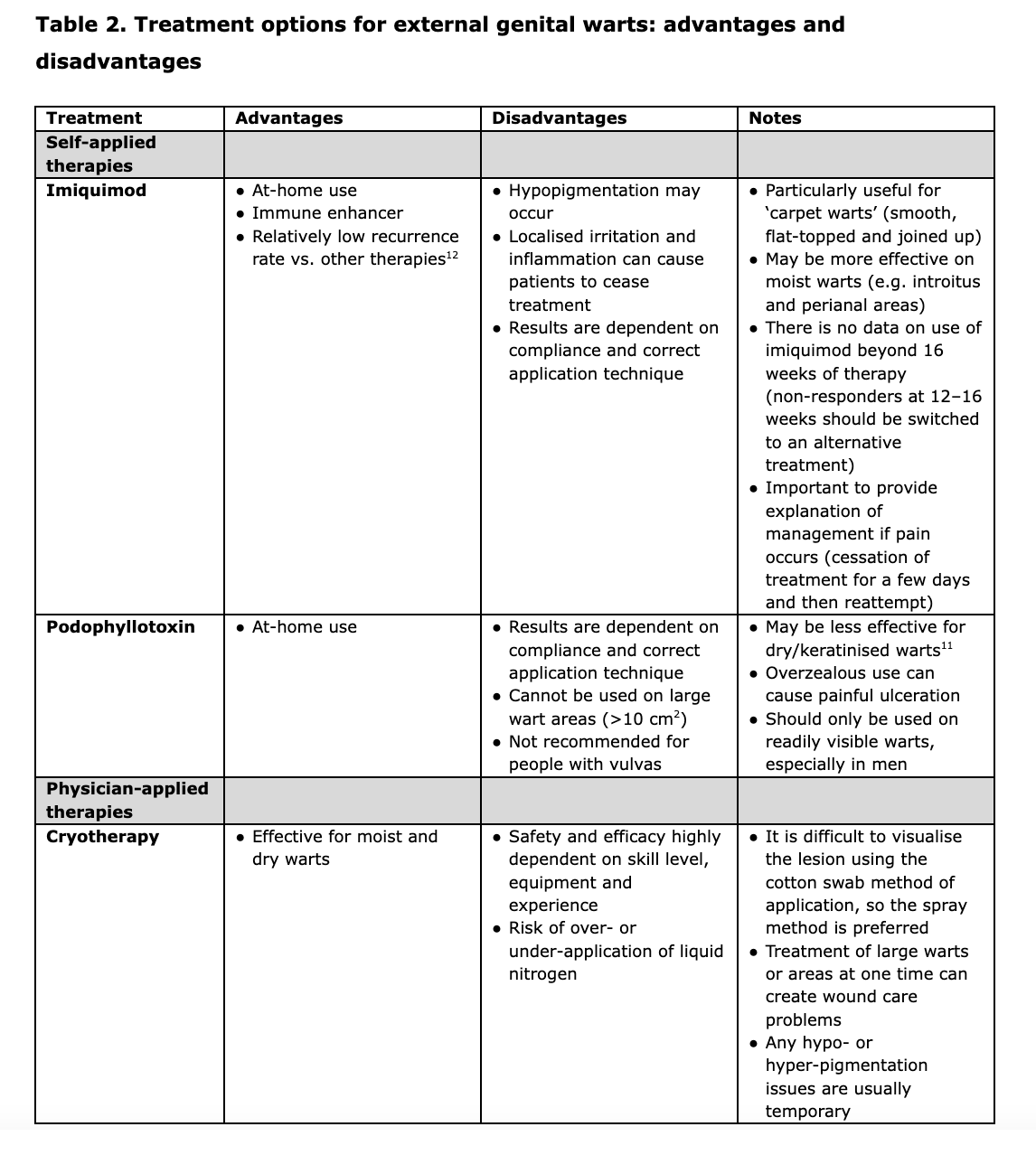

Treatment of genital warts, especially complex cases, is an art. Specialist consultation is recommended for difficult-to-treat cases. Treatment options include self-applied therapies (imiquimod and podophyllotoxin) and physician-applied therapies (cryotherapy, curettage and excision, electrocautery or diathermy [hyfrecation], laser therapy, and trichloroacetic acid [TCA]). Treatment with podophyllin resin, 5% fluorouracil cream or systemic interferon is not recommended due to side effects, toxicity and difficulty in application.

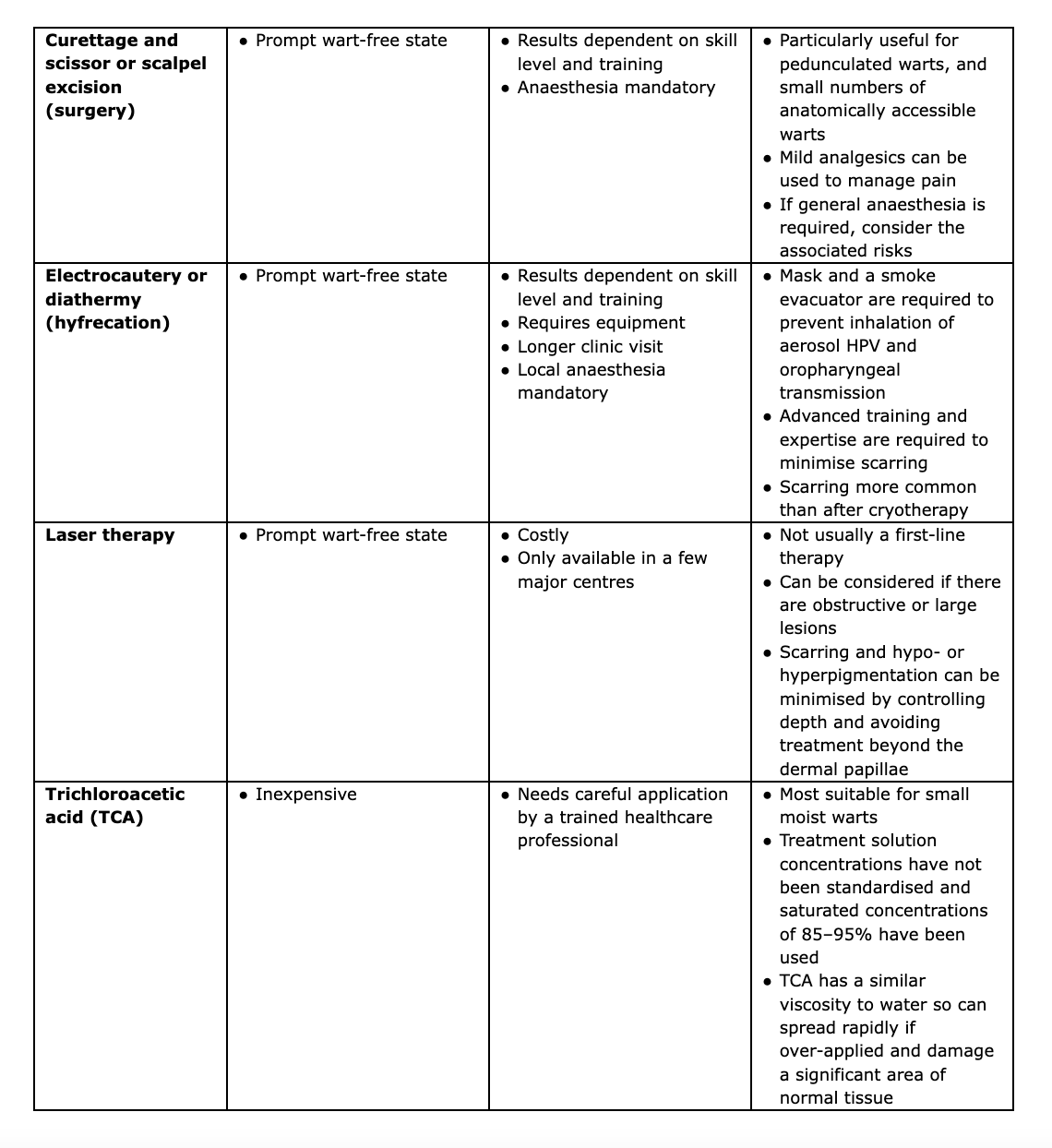

Key details regarding the mechanism of action, indication, application, contraindications and side effects for all the options listed above are shown in Table 1, and the advantages and disadvantages of each approach are summarised in Table 2.

Treatment recommendations

- The goal of treatment for genital warts is the removal of visible warts. Grade C

- Standard therapies for genital warts can eventually remove most warts, although no one treatment is ideal for all warts or all individuals.

Grade A & C - Clinicians should be knowledgeable about, and have available to them, at least one self-applied treatment and one healthcare provider-administered therapy. Grade C

Treatment selection

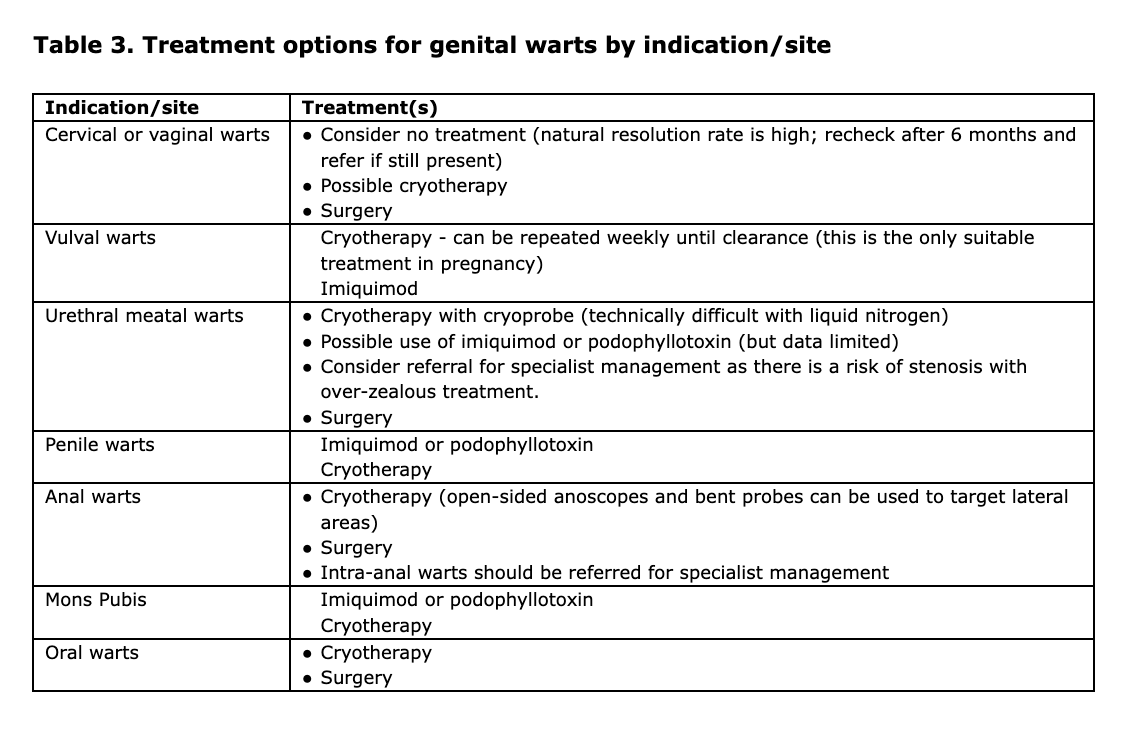

The most appropriate treatment option(s) for external genital warts by indication/site are summarised in Table 3. Most treatment modalities are eventually effective in eliminating small numbers of warts. Patients with limited disease (i.e. one to five warts) may benefit most from cryotherapy or simple office surgery. Ablative therapy (cryotherapy) should be considered in those with large or extensive areas of warts to at least debulk their warts (although ablative treatment, especially to the introitus, can result in disabling chronic pain syndrome or hyperaesthesia at the treatment site).

For self-applied therapeutic modalities, treatment beyond the manufacturer’s recommendations is not advisable and concurrent use of multiple therapeutic modalities on a single wart is not recommended as routine treatment because of a lack of data showing that this improves clearance or recurrence rates. However, possible combinations include the use of podophyllotoxin after cryotherapy, and the combination of laser therapy and imiquimod (which has been shown to be safe and well tolerated(13)). A change of treatment modality or onward referral should be considered if there has not been any significant response to treatment within 4–6 weeks (continuing lack of response might indicate other pathology and the need for further assessment).

Surgical removal of warts, by diathermy, laser ablation or excision under local or general anaesthesia, may render an individual wart-free, usually in a single visit. However, the disadvantages are that significant training, specific equipment, and a longer clinic visit are required. Although surgery is of most benefit when warts are present in large numbers or over large surface areas, it also has a role in other cases. While the cost of a single surgical visit may be higher, surgery can accomplish in one visit what often requires multiple visits for other ablative modalities, which may result in greater cost effectiveness for some individuals. However, recurrence rates might be the same as other therapeutic modalities and the morbidity of treatment may be greater, with increased risk of pain, infection and scarring.

Treatment of immunocompromised individuals

Management of immunocompromised individuals with genital warts should be performed in consultation with a sexual health specialist and any other specialists involved in the care of that individual.

Persons who are immunocompromised due to concurrent HIV infection or other causes may respond less well to therapy for genital warts than immunocompetent individuals, and may have more frequent recurrences after treatment.(1) Squamous cell carcinomas arising in squamous intraepithelial lesions resembling genital warts are more common in immunosuppressed individuals. Immunosuppressed women should undergo annual cervical screening, with early referral for colposcopy if abnormalities are detected.

Although not contraindicated, imiquimod should be used with caution in individuals with autoimmune conditions or those taking systemic immunosuppressants, although systemic absorption from topical treatment is likely to be negligible.

Therapy management

The response to treatment should be continually evaluated to avoid over-treatment and a therapeutic course that is worse than the disease itself. There are several things that can make a course of treatment less painful and stressful for individuals. Saltwater baths can help soothe and heal the genital area during treatment (put two handfuls of plain salt per bath or two tablespoons in a large bowl, preferably twice daily, and then dry the area with a hairdryer). Local anaesthesia using lignocaine gel 2% (Xylocaine) can be applied to raw areas two minutes prior to micturition and defaecation to reduce discomfort. For large areas made raw by wart ablations, 1% silver sulphadiazine cream is useful. Furthermore, a concomitant yeast infection is common, which can be managed using local imidazole preparations and/or oral fluconazole.

Emerging or alternative therapies

A number of ablative therapies have been trialled in the destruction of anogenital warts. Sinecatechins (an active product of green tea extract) inhibits telomerase production via its role in cell signalling pathways, and is approved for the treatment of genital warts in the US.(1) Other treatment options being investigated include photodynamic therapy and intralesional immunotherapy.(14)

HPV vaccine as therapy

It is not yet clear whether administration of the HPV vaccine to individuals who already have HPV infection alters the natural history of infection. For example, does vaccination result in faster clearance (or undetectability), reduce viral persistence, or prevent disease recurrence? Several trials are assessing the benefit of adjuvant HPV vaccination in people being treated for high grade CIN.(15-17)

Unvaccinated individuals attending colposcopy clinics who are eligible for funded HPV vaccine should be offered it because this will protect against the acquisition of new HPV types, and may protect against recurrent CIN. Older people may benefit from adjuvant vaccine after treatment for CIN, but this would need to be self-funded.

Post-treatment follow-up

The benefit, frequency, interval and type of follow-up care necessary after treatment of genital warts has not been studied. Follow-up evaluation can provide the opportunity for education and counselling. The need to monitor for complications of therapy will vary based on the experience and cognitive ability of the affected individual, the number and location of warts, and the treatment modality used. Individuals concerned about recurrences could be offered an evaluation 3 months after successful treatment because most recurrences occur during this period. Recurrence of warts is much more common in immunosuppressed individuals and periodic follow-up evaluation may be necessary. Management of genital warts must include careful assessment and testing for other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), depending on the patient’s sexual history, because individuals with genital warts are at risk of other STIs.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment Guidelines, 2021. Genital Warts. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/anogenital-warts.htm.

- Ho GY, Bierman R, Beardsley L, Chang CJ, Burk RD. Natural history of cervicovaginal papillomavirus infection in young women. N Engl J Med 1998; 338 (7): 423-8.

- Lynch P. Skin coloured lesions. In: Edwards L, Lynch P, eds. Genital Dermatology Atlas. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011.

- Bunker C, Neill S. Male genital dermatology. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths CEM, eds. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology: Blackwell Publishing; 2004.

- Burkhart CG. The endogenous, exogenous, and latent infections with human papillomavirus. Int J Dermatol 2004; 43 (7): 548-9.

- Sterling J. Anogenital warts. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths CEM, eds. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology: Blackwell Publishing; 2004.

- Bornstein J, Bogliatto F, Haefner HK, et al. The 2015 International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD) Terminology of Vulvar Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2016; 20 (1): 11-4.

- Bunker C, Neill S. Female genital dermatology. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths CEM, eds. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology: Blackwell Publishing; 2004.

- Sterling J. Vulval intraepithelial neoplasia, penile intraepithelial neoplasia and Bowenoid papulosis. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths CEM, eds. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology: Blackwell Publishing; 2004.

- Bunker C, Neill S. Eythroplasia of Queyrat, Bowen's disease of the penis and bowenoid papulosis. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths CEM, eds. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology: Blackwell Publishing; 2004.

- Gilson R, Nugent D, Werner RN, Ballesteros J, Ross J. 2019 IUSTI-Europe guideline for the management of anogenital warts. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34 (8): 1644-53.

- Grillo-Ardila CF, Angel-Müller E, Salazar-Díaz LC, Gaitán HG, Ruiz-Parra AI, Lethaby A. Imiquimod for anogenital warts in non-immunocompromised adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; (11): Cd010389.

- Gunter J. Genital and perianal warts: new treatment opportunities for human papillomavirus infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003; 189 (3 Suppl): S3-11.

- Muñoz-Santos C, Pigem R, Alsina M. New treatments for human papillomavirus infection. Actas Dermosifiliogr 2013; 104 (10): 883-9.

- Imperial College London. The NOVEL trial. Available at: https://www.thenoveltrial.org.

- Kechagias KS, Kalliala I, Bowden SJ, et al. Role of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination on HPV infection and recurrence of HPV related disease after local surgical treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2022; 378: e070135.

- van de Laar RLO, Hofhuis W, Duijnhoven RG, et al. Adjuvant VACcination against HPV in surgical treatment of Cervical Intra-epithelial Neoplasia (VACCIN study) a study protocol for a randomised controlled trial.

BMC Cancer 2020;

20 (1): 539.