Management of First Clinical Episode

Definitions:

First episode: First episode with either herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) or type 2 (HSV-2). Dependent on whether the individual has had prior exposure to the other type, this is further subdivided into:

Primary infection: First infection with either HSV-1 or HSV-2 in an individual with no pre-existing antibodies to either type.

Non-primary infection: First infection with either HSV- 1 or HSV-2 in an individual with pre-existing antibodies to the other type.

| KEY POINTS |

|---|

| The first clinical episode may, but does not always, reflect recent infection. |

| The first episode of genital herpes is generally more severe and/or more prolonged than subsequent episodes. |

| If genital herpes is suspected, oral antiviral medications should be started immediately. |

| PCR swab confirmation of infection is important, but should not delay the initiation of treatment. |

| Oral antiviral therapy substantially reduces the duration and intensity of symptoms. |

| The severity of symptoms differs markedly between individuals, but lesions can last up to 3 weeks in some cases. |

| Consider anticipatory prescription of episodic treatment for potential future outbreaks. |

The first clinical episode of genital HSV-1 or HSV-2 infection may indicate a recent acquisition of the virus, but this is not always the case. It could also represent a primary HSV infection, a new non-primary infection, or the first recognised clinical manifestation of a previously acquired infection. Patients with a first clinical episode of HSV infection are often very unwell and therapy should be started regardless of how long the lesions have been present and before virological confirmation. Systemic and local symptoms can last up to 2–3 weeks if left untreated. Oral antiviral therapy substantially reduces the duration and intensity of symptoms.(1, 2) GRADE A.

Clinical features, examination and diagnosis

Clinical features

Most people infected with HSV are asymptomatic or do not recognise their symptoms as genital herpes. If they do develop:

Symptoms

- Local symptoms can consist of painful anogenital ulceration, dysuria and less commonly, pruritus, vaginal or urethral and anal discharge.

- Flu-like systemic symptoms; fever, headache and myalgia and are much more common in the primary first clinical episode when compared to recurrences or non-primary episodes.

- Rarely systemic symptoms are present i.e meningitis, headaches, and generalised myalgia.

- Severe anal pain, tenesmus, bleeding, constipation, difficulty urinating and sacral paraesthesia are associated with Herpes Proctitis (see complications of genital herpes below for further information and management).

Signs

- External ano-genital blistering and ulceration. These signs can also be present on the cervix and rectal mucosa.

- Typically vesicles form into ulcers which then develop a crust and heal with no sign of scarring.

- Atypical skin lesions can also occur and be mistaken for linear skin splits or fissuring more commonly associated with a localised skin condition.

- Tender, bilateral, inguinal lymphadenitis is common.

- In recurrences lesions usually affect a favoured site and are unilateral and are limited to the infected dermatome.

- Herpetic lesions can occasionally occur on extragenital sites i.e finger, thigh, buttock. This occurs through skin to skin contact from skin which is shedding the virus and a break in the skin at the recipient skin site. Autoinoculation is rare but also possible.

- In herpes proctitis on endoscopic examination the distal rectum shows convalescing vesicles and pustules, mucosal ulceration and oedema. External HSV lesions are absent in the majority of cases.

Physical examination

Examination should include inspection of the anogenital skin and checking if genital lymph nodes are enlarged; speculum examination can be delayed if discomfort is anticipated.

Diagnosis

Clinical diagnosis alone is not very accurate - due to atypical genital herpes presentation, especially with recurrences. A high level of suspicion needs to be had with tender or crusted breaks in the skin in the anogenital region. Diagnosis is obtained by undertaking a viral PCR swab of the lesion. Obtaining a swab in early infection is more likely to avoid a false negative result. A negative PCR test result does not necessarily exclude a diagnosis of HSV (see Epidemiology, Transmission, and Diagnosis chapter for more details). PCR swab confirmation of HSV infection is important, but should not delay the initiation of treatment. Anyone presenting with symptoms of proctitis should have a rectal swab taken for the detection of HSV. Patients with proctitis should be treated and referred urgently to a specialist.

Differential diagnoses

There are several alternative differential diagnoses that should be considered in the evaluation of an individual with suspected genital herpes:

- Other genital infections: these lack the preceding vesicular stage, apart from varicella zoster infection which is unilateral. Consider syphilis and Mpox

- Candidiasis and folliculitis

- Aphthous ulcers: there are fewer and larger lesions with no preceding vesicles.

- Autoimmune blistering disorders: these include pemphigus and cicatricial pemphigoid, which are usually chronic.

Complications of primary genital herpes

Any patient with complications of HSV infection should be reviewed by the appropriate specialist as indicated.

Neurological Complications

Neurological complications of genital herpes occur more often than is often recognised. These include acute lymphocytic meningitis, which is generally benign. HSV-2 infection is associated with aseptic meningitis in up to 36% of adult women and 13% of men with primary HSV-2 infection.3 Symptoms include neck stiffness, low-grade fever and severe headache. Diagnostic features include photophobia, increased white cell count, elevated protein levels, and a positive HSV-2 PCR result for a cerebrospinal fluid sample.(3)

Acute radiculitis

Another potential complication is acute radiculitis (herpetic lumbosacral radiculoneuropathy or Elsberg syndrome), which is a diagnosis that tends to be overlooked. However, acute radiculitis may cause acute urinary retention, constipation and sacral neuralgia. Referred pain can affect the saddle area distribution (S3 and S4) of the sacral nerve and the bladder detrusor muscle. Erectile dysfunction (in males), dull or severe burning pain in the anogenital region, loss of sensation and hypersensitivity can occur down the thighs and lower legs. Acute radiculitis is usually self-limiting and tends to resolve in 1–2 weeks, but supportive care should be offered (analgesia, gabapentinoids or tricyclic antidepressants may be useful). Symptoms sometimes persist for weeks, and in rare instances opiate analgesia may be required to manage severe intractable pain. HSV-2-related myelo-radiculitis, associated with advanced immunosuppression and AIDS, may be associated with a fatal outcome.(4)

Bell’s Palsy

The symptoms of Bell’s palsy can be caused by varicella zoster virus, HSV-1, or (rarely) HSV-2. Early treatment with oral steroids is effective.(5, 6) A 2019 Cochrane review concluded that antiviral treatment increases the proportion of patients who have recovered at 3- and 12-month follow-up compared with steroids alone, but the evidence quality is low.

Encephalitis

Sporadic herpes simplex encephalitis is an acute necrotising viral encephalitis that is most often caused by primary infection with HSV-1. Clinical features are usually nonspecific (similar to all forms of encephalitis) and include headache, signs of meningeal irritation, altered mental status, and seizures.

Erythema Multiforme

HSV (especially Type 1) is a common trigger for erythema multiforme, which can develop 3–14 days after HSV infection. Mild forms of erythema multiforme are common, with macules, papules and urticarial lesions of up to 3 cm on the extremities. These lesions particularly affect the hands and feet, the top surface of the elbows and knees, and (less often) the trunk. Some lesions develop into the classical “target” lesion with three colour zones: central dusky erythema, surrounded by a paler oedematous zone and an outer erythematous ring with a well-defined border. These usually resolve within 7–10 days.

Viremia

Infrequently, HSV viraemia may result in infection of visceral organs. In most cases of disseminated infection, lesions are confined to the skin, but hepatitis, pneumonitis and other organ involvement may occur, with or without vesicular skin lesions.

Proctitis

Although most studies have looked at herpes proctitis in the MSM population, it is likely that any receptive partner of anal exposure (oral-anal, genital-anal, digital-anal) could develop HSV proctitis. HSV is a significant cause of proctitis in men who have sex with men (MSM). HSV-1 and HSV-2 are both associated with proctitis. A retrospective review in the USA found that 16% of MSM with proctitis had HSV detected by culture methods, and that 3% had herpes in addition to another rectal STI.(7) Herpes proctitis can be a primary infection or a reactivation of HSV-1 or HSV-2 but most clinical presentations are a primary infection.(8) In an Australian study HSV-2 was causative for 22% of HIV-positive MSM with proctitis and 12% of HIV-negative MSM while HSV-1 was found in 14% HIV-positive and 6.5% HIV-negative MSM.(9)

Signs and symptoms of herpes associated proctitis include: severe anal pain, tenesmus, painful anogenital vesicles, bleeding, constipation, difficulty urinating and sacral paraesthesia. On endoscopic examination the distal rectum shows convalescing vesicles and pustules, mucosal ulceration and oedema. External HSV lesions are absent in the majority of cases, with only 30% of MSM with HSV proctitis having visible external anal ulceration.(9)

Obtain blind anal/rectal swab for diagnostic purposes. Starting HSV antiviral therapy prior to virological confirmation is recommended in people with proctitis with severe pain and especially in the MSM and HIV positive people.(10) Recommended treatment for herpes proctitis is supportive cares and oral antiviral medication; valaciclovir 1 g orally twice daily 7-10 days or alternatively, aciclovir 400 mg orally 3 times daily 7 -10 days.(11) Herpes proctitis can recur and suppressive therapy should be considered on a case by case basis in discussion with the patient.

Treatment of a first episode of genital herpes

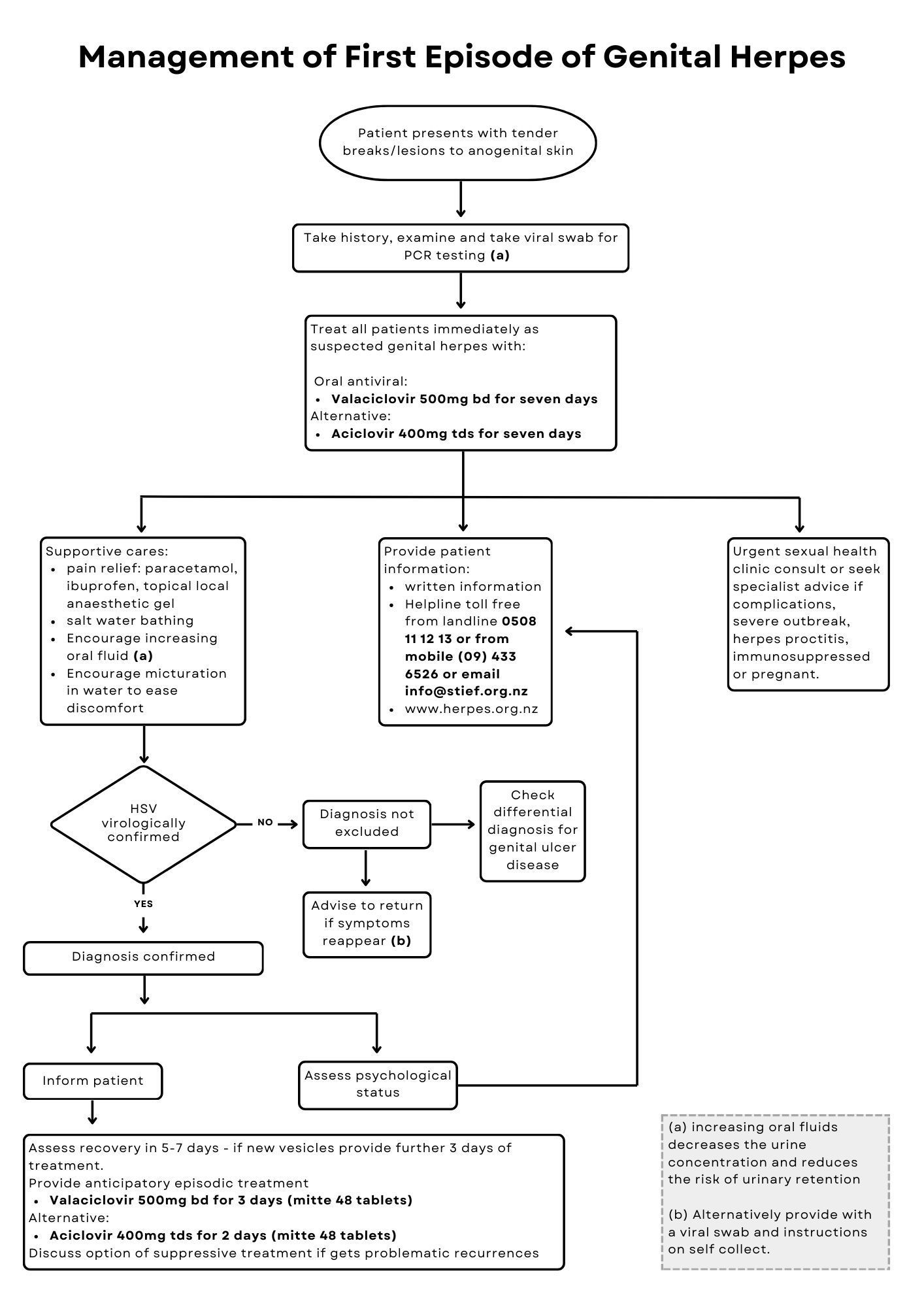

A treatment algorithm for a first episode of genital herpes is shown in Figure 1.

Pharmacological treatment

If there is a possibility of pregnancy or known pregnancy, please refer to the Genital Herpes in Pregnancy document for details of approaches to antiviral therapy in this population. Immunocompromised individuals, or those with herpetic proctitis, should be referred to the appropriate specialist.

1. Oral antivirals

Preferred regimen:

- Valaciclovir 500 mg twice daily for 7 days

Alternate regimen:

- Aciclovir 400 mg three times daily for 7 days

Immunocompromised individual regimens (under specialist guidance):

- Valaciclovir 500 mg - 1000 mg twice daily for 10 days

OR:

- Aciclovir 400 mg five times daily for 7-10 days

Lesions may not completely heal over, and mild neurological symptoms may not fully resolve during the course of drug treatment. Nevertheless, an additional further course of therapy is not usually indicated unless new lesions continue to appear. Give an extended course (usually an additional 3 days) of antiviral medication if new lesions are still developing at the end of the 7 day course.

Consider prescribing “backpocket” episodic medication for patients at the time of diagnosis (episodic treatment needs to be started very promptly to be effective).

Suggested “Back-pocket” episodic regimen and supply:

- Valaciclovir 500 mg twice daily for 3 days (mitte 48 tablets, this will cover 8 recurrences)

Alternative:

- Aciclovir 800mg three times daily for 2 days (mitte 48 tablets)

An increasing number of pharmacists are able to supply an episodic course of antiviral medication for people with a recurrence of facial or genital herpes which may be helpful in situations where patients are unable to access timely appointments with their healthcare provider.

2. Intravenous antivirals

Intravenous (IV) aciclovir therapy can be considered for patients who have severe disease or complications that necessitate hospitalisation.(12)

Aciclovir 5-10 mg/kg every 8 hours for 2-7 days (followed by oral treatment to complete at least a 10 day course of antiviral therapy).

3. Topical antivirals

Topical aciclovir creams are not recommended because they offer minimal clinical benefit.

Supportive cares

In addition to oral antivirals, other measures can be used to control symptoms. In the first episode of genital herpes supportive cares are an adjunctive to antiviral medication. Regular paracetamol and ibuprofen is usually adequate analgesia for genital herpes, however, patients with significant pain may benefit from a course of codeine or paracodeine as appropriate. Helping patients avoid admission to hospital due to urinary retention requires advice on increasing fluids to ensure the urine is dilute, encouraging micturition under water, such as a bath or shower and the potential use of topical 2% lignocaine gel. The lignocaine gel has an anesthetic effect after 5 minutes and lasts up to half an hour. A saline soak can give pain relief and promote healing; the recipe is half a cup of household salt in the bath or 2 teaspoons per litre of warm water. Ice packs can also be soothing. Discourage patients washing their genital area with soap, body wash or antiseptic solutions. GRADE C

Education and follow up

Follow-up after a first episode of genital herpes can be offered if there are ongoing symptoms or if the patient requires psychosocial support. For some individuals, one visit may not be enough to properly manage the implications of a genital herpes diagnosis.

It is important to ensure that patients receive accurate, up-to-date information about genital herpes. A range of printed materials can be downloaded from the NZHF website, or ordered at no cost. Patients can also be made aware of the Herpes Helpline (tollfree 0508 11 12 13 from a landline or 09 433 6526 from a mobile). This telephone service is staffed by trained professionals who can provide counselling and education around a HSV diagnosis.

To help health providers in giving a genital herpes diagnosis the 3-minute patient tool on the NZHF website may be useful. Even with the help of written material such as the NZHF Myth vs Facts leaflet and The Facts booklet, some patients may benefit from a follow up appointment, or call, to answer their questions. GRADE C

Anticipatory episodic antiviral therapy is recommended, and management is more effective when individuals have a prescription or drug supply to hand and start therapy themselves at the first signs of a recurrence. GRADE A

See the

Counselling a Diagnosis chapter for more detailed information.

References

- Bryson YJ, Dillon M, Lovett M, et al. Treatment of first episodes of genital herpes simplex virus infection with oral acyclovir. A randomized double-blind controlled trial in normal subjects. N Engl J Med 1983; 308 (16): 916-21.

- Mertz GJ, Critchlow CW, Benedetti J, et al. Double-blind placebo-controlled trial of oral acyclovir in first-episode genital herpes simplex virus infection. JAMA 1984; 252 (9): 1147-51.

- Berger JR, Houff S. Neurological complications of herpes simplex virus type 2 infection. Arch Neurol 2008; 65 (5): 596-600.

- Corey L, Adams HG, Brown ZA, Holmes KK. Genital herpes simplex virus infections: clinical manifestations, course, and complications. Ann Intern Med 1983; 98 (6): 958-72.

- Engström M, Berg T, Stjernquist-Desatnik A, et al. Prednisolone and valaciclovir in Bell's palsy: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet Neurol 2008; 7 (11): 993-1000.

- Sullivan F, Daly F, Gagyor I. Antiviral Agents Added to Corticosteroids for Early Treatment of Adults With Acute Idiopathic Facial Nerve Paralysis (Bell Palsy). JAMA 2016; 316 (8): 874-5.

- Klausner JD, Kohn R, Kent C. Etiology of clinical proctitis among men who have sex with men. Clin Infect Dis 2004; 38 (2): 300–302.

- Hoentjen F, Rubin DT. Infectious proctitis: when to suspect it is not inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis and Sci 2012; 57 (2): 269–273.

- Bissessor M, Fairley CK, Denham I, et al. The etiology of infectious proctitis in men who have sex with men differs according to HIV status. Sex Transm Dis 2013; 40 (10): 768–770.

- de Vries, HJC, Nori AV, Larsen HK, et al. 2021 European Guideline on the management of proctitis, proctocolitis and enteritis caused by sexually transmissible pathogens. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2021; 35 (7): 1434-1443.

- Sigle GW, Kim R. Sexually transmitted proctitis. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2015; 28 (2): 70-8.

- Beauman JG. Genital herpes: a review. Am Fam Physician 2005; 72 (8): 1527-34.