GENITAL HERPES IN PREGNANCY

This chapter was updated in October 2025, in line with international guidelines.

| KEY POINTS |

|---|

| At the first antenatal appointment (and again later if appropriate) all pregnant people should receive information and have a discussion about infections that may affect the baby during pregnancy or birth, including herpes simplex virus. This should occur regardless of whether or not they are already known to have herpes simplex virus (HSV). |

| Primary HSV infection in pregnancy carries a higher risk of viraemia compared with infection in non-pregnant people. Herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection should be considered in differential diagnosis of an acutely unwell pregnant person. |

| Specialist obstetric and paediatric advice should be sought for those with a first episode of genital herpes that occurs in the third trimester, or any active recurrent lesions at delivery. These situations are at high risk of maternal-fetal transmission of HSV, and delivery by Caesarean section is indicated for primary or non-primary first episodes within 6 weeks of delivery, and may be considered for recurrent lesions at term after shared decision-making. |

| Those with a history of genital herpes who have not experienced any recurrences during pregnancy can be reassured that the risk of maternal-fetal transmission is extremely low (<0.04%);(1, 2) maternal antibodies are protective for the fetus/neonate. |

| Recurrent lesions (genital HSV acquired prior to pregnancy or in the first and second trimester) at term are a relative (not absolute) indication for delivery by Caesarean section. The risk of maternal-fetal transmission from recurrent lesions during labour is low (1-3%), although risk may be greater with HSV-1 than HSV-2. Management options should be discussed with affected individuals antenatally. |

| In the setting of a vaginal delivery (expected or unexpected), scalp electrodes and instruments should be avoided if lesions are present. Unless there is a clear indication because skin trauma may increase the risk of HSV transmission. Use external CTG where possible. |

| Antiviral medications, especially aciclovir, have been widely used in pregnancy without apparent adverse consequences. In general, pregnant people with genital herpes (in any trimester) should be offered antiviral treatment after a discussion regarding the relative benefits versus possible disadvantages. |

| Suppressive antiviral therapy given from 36 weeks of gestation may reduce the chance of a recurrence at term (initiate earlier in the gestation if there is a risk of preterm birth). A higher frequency dosing regimen is recommended at this time because of the increased plasma volume in pregnancy. |

| Caesarean section and antivirals reduce but do not eliminate transmission risk. |

| All people should be given the same advice on postnatal surveillance of their baby/babies irrespective of whether antiviral treatment was given or the mode of delivery (see also the chapter on Neonatal HSV Infection). |

| Most genital HSV infections (primary, non-primary or recurrent HSV-1 or HSV-2) are asymptomatic. i.e. most mothers of infants with neonatal HSV infection were previously unaware of their own infection before the baby's diagnosis. |

Impact on pregnancy outcomes

Primary maternal genital herpes infection in early pregnancy may be associated with miscarriage,(3) and in the second and third trimesters might be associated with preterm delivery. In recurrent maternal HSV infection, the risk of intrauterine fetal infection is extremely low.(4) Furthermore, antenatal recurrent disease without HSV shedding at delivery is rarely associated with adverse neonatal outcomes. However, the presence of symptoms at delivery correlates relatively poorly with the detection of HSV from genital sites or lesions by HSV polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Assessment of viral shedding is based on clinical assessment.(5) If active recurrent genital herpes is present at delivery there is a 1-3% risk of maternal transmission. If active primary herpes present at delivery there is a high risk of maternal transmission (25–50%).

A nested case-control serology study assessing HSV-2 antibodies in stored serum samples from 283 women with a fetal loss after 20 weeks compared with 970 randomly selected women from a large source population found no association between HSV infection and fetal loss.(6) Data from a US cohort study found that untreated recurrent genital herpes infection may predispose to preterm delivery, but that this risk is eliminated by the use of suppressive antiviral treatment.(7)

Use of antivirals in pregnancy and breastfeeding

Antiviral therapy is indicated for the treatment of primary and recurrent episodes of genital herpes during pregnancy (as for non-pregnant people) and for prophylaxis to reduce the risk of recurrence at the time of delivery. In the majority of situations, the benefits of antiviral therapy outweigh possible risks.

Aciclovir has been widely used in pregnancy. There is less experience with valaciclovir, but it is expected that this would be safe because valaciclovir is a prodrug of aciclovir. Consider the use of suppressive antiviral therapy from 36 weeks in people with multiple, recurrent, overt lesions or prior to 36 weeks if frequent symptomatic recurrences; if there is a risk of preterm birth it would be reasonable to initiate suppression therapy at an earlier gestation, attempting to cover at least 4 weeks prior to birth. It is recommended to use a higher frequency dosing regimen in late pregnancy because of the increased plasma volume in pregnancy. Aciclovir/valaciclovir is safe in breastfeeding (milk transfer <1% infant dose). If HSV lesions are present on the breast: avoid feeding from that breast, discard expressed milk, and use strict hygiene. Suppressive antivirals may be used for recurrent breast lesions.

Commonly used regimens are as follows.

Primary/first episode therapy:

1. Oral antivirals

First episode preferred regimens:

- Valaciclovir 500 mg twice daily for 7 days

Alternative regimens:

- Aciclovir 400 mg three times for daily 7 days

If the primary outbreak occurs in the first or second trimester, consider prescribing “backpocket” episodic medication for patients at the time of diagnosis (episodic treatment needs to be started very promptly to be effective).

Suggested “Back-pocket” episodic regimen and supply:

- Valaciclovir 500 mg twice daily for 3 days

(supply 48 tablets, sufficient for 8 recurrences).

2. Intravenous antivirals

Intravenous (IV) aciclovir therapy can be considered for patients who have severe disease or complications that necessitate hospitalisation.(7)

- Aciclovir 5-10 mg/kg every 8 hours for 2-7 days (followed by oral treatment to complete at least a 10 day course of antiviral therapy).

Suppressive therapy in recurrent disease in pregnant people before 36 weeks gestation or whom are breastfeeding:

Preferred regimens:

- Valaciclovir 500 mg once a day

If recurrences not well controlled on this regime then consider changing to:

- Valaciclovir 500 mg twice daily

Alternative regimens:

- Aciclovir 400 mg twice daily

If recurrences not well controlled on this regime then consider changing to:

- Aciclovir 400 mg three times daily

Note: In the second and early third trimesters of pregnancy valaciclovir 500mg twice daily OR aciclovir 400 mg 3 times daily should be considered because of increased plasma volume, but see below for suppression from 36 weeks’ gestation.

Suppressive therapy in recurrent infection in pregnant people from 36 weeks of gestation:

- Valaciclovir 500 mg twice daily until delivery; seek specialist advice if breakthrough episodes occur.

- Oral aciclovir 400 mg three times daily until delivery; seek specialist advice if breakthrough episodes occur.

Key evidence relating to the use of antivirals in pregnancy is summarised below.

- Registry data (1984-99) collected from 1234 infants exposed to aciclovir in pregnancy and a Danish cohort study of 1804 infants exposed to aciclovir, valaciclovir or famciclovir during the first trimester of pregnancy did not show any increase in the overall rate of birth defects compared with the general population.(8, 9) These data are reassuring, but the sample sizes were insufficient to assess the relative risk of specific defects.

- Small studies have shown that the prophylactic use of aciclovir from 36 weeks’ gestation decreases the number of clinical recurrences and reduces the need for Caesarean section, but does not completely eliminate viral shedding.(10-13) Two meta-analyses have reported that prophylactic therapy reduces clinical recurrences at delivery, decreases in the need for Caesarean section for active herpes, and reduces viral shedding.(14, 15) GRADE B

- Because the risk of maternal-fetal transmission is high when primary infection is acquired within the third trimester, maternal and neonatal aciclovir therapy should be considered if there has been membrane rupture for more than 4 hours or where a vaginal delivery is unavoidable.(16)

- Aciclovir is categorised as B3 in the Australian TGA Prescribing Medicines in Pregnancy database (drugs that have been taken by only a limited number of pregnant people and those of childbearing age, without an increase in the frequency of malformation or other direct or indirect harmful effects on the human fetus having been observed OR studies in animals have shown evidence of an increased occurrence of fetal damage, the significance of which is considered uncertain in humans).(17)

- A US case-control study raised the possibility of an increased risk of gastroschisis due to antiherpetic medication use in early pregnancy or the underlying genital herpes infection that was being treated, more research is needed to determine the actual risk, as the aetiology of gastroschisis is multifactoral.(18)

- There are theoretical concerns that maternal antiviral therapy may suppress rather than treat infections in infants, thus delaying the presentation of neonatal disease.

- Use of aciclovir and valaciclovir (which converts into aciclovir after ingestion) for treating first episode or recurrent genital herpes in those who are breastfeeding is approved by the American Academy of Pediatrics.(19) GRADE B Even at the maximum maternal doses, the amount of aciclovir in breast milk is only about 1% of a standard infant dose, making it unlikely to cause any adverse effects in breastfed infants.(20)

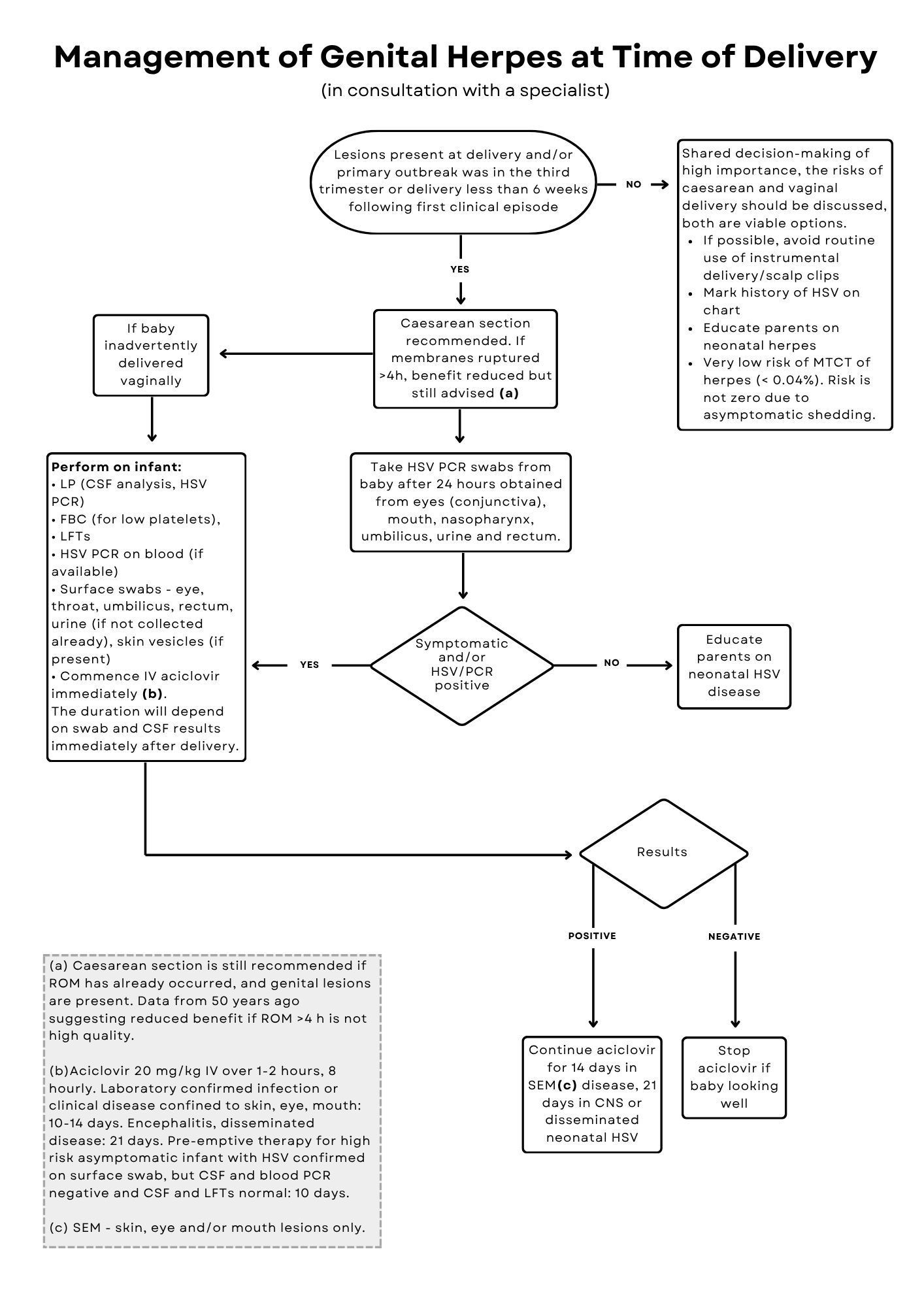

Mode of delivery

There are no randomised controlled trial data to guide the optimal delivery management for pregnant people with genital herpes. In those with primary infection late in pregnancy or at the time of delivery, Caesarean section significantly reduces vertical transmission in people with primary infection,(2) but does not eliminate the risk as infection has occurred in the presence of intact membranes. Prolonged contact with infected secretions may further reduce the benefits of Caesarean delivery.(21) The benefit of Caesarean delivery in people who have recurrent episodes at the time of labour is debatable because the risk of vertical transmission in recurrent disease is low. This decision should be made with the pregnant person and the appropriate specialists. If there are no lesions and the primary infection was prior to pregnancy or early in the pregnancy then vaginal delivery is appropriate.

No definitive studies have investigated the relationship between the duration of rupture of membranes (ROM) in the presence of clinical lesions and HSV transmission to the fetus. Caesarean section is still recommended if ROM has already occurred, and genital lesions are present. Data from 50 years ago suggesting reduced benefit if ROM >4 hours is not high quality.(22)

Key evidence relating to the impact of mode of delivery on maternal-fetal HSV transmission is summarised below.

- Of 31,663 women from the US who had serum samples taken during labour, 202 were found to have HSV, and neonatal transmission occurred in 10/202 (5%).(2) The HSV transmission rate was 1.2% after Caesarean delivery versus 7.7% after vaginal delivery (p=0.047). Risk factors for neonatal HSV infection included a first-episode HSV infection, isolation of HSV-1 versus HSV-2, use of invasive monitoring, premature delivery, and young maternal age.

- Pooled data from the above study and two other cohorts (from the USA and Sweden) showed that HSV-1 was more readily transmissible to the neonate than HSV-2, and that maternal HSV-1 antibodies do not offer significant protection against HSV-2.(23)

- In the Netherlands, it has been the policy not to offer Caesarean section to women with a HSV recurrence at term since 1987 and this has not resulted in an increase in the incidence of neonatal HSV infection (19 cases 1987–1991 versus 26 cases in 1981–1986 before the policy change).(12) A follow-up audit for 1999 to 2005 also found a low rate of neonatal HSV infection in the Netherlands despite the small number of Caesarean section deliveries performed in pregnant women with HSV.(24) A higher rate of neonatal HSV infection in the Netherlands from 2006 to 2011 was attributed to poor adherence to the guideline recommending Caesarean section for women with primary HSV infection in late pregnancy.(25)

- UK guidelines recommend that people who have signs or symptoms of a recurrent HSV infection during labour should be offered a Caesarean section, but this is not an absolute indication for Caesarean delivery.(22)

Overall, there is a lack of robust evidence to inform the management of people who have recurrent genital herpes lesions at the onset of labour. Delivery by Caesarean section has traditionally been an option, but discussion about the relative risks of vaginal versus Caesarean delivery should ideally take place during the antenatal period. Because the risk of transmission during recurrent infection is low (1–3%) some people may opt for a vaginal delivery. Factors such as prematurity, infection with HSV-1 rather than HSV-2, and an expected long labour may increase the risk of maternal-fetal HSV transmission, and should be taken into account in discussions about the most appropriate strategy for each individual.

Special situations in pregnancy

Disseminated infection

Disseminated HSV infection after genital or oro-labial infection is rare, but may be life-threatening. The diagnosis of disseminated HSV disease should be considered in any unwell pregnant person with a sepsis-like illness or with deranged or worsening liver function tests. Viraemia during primary infection in a pregnant person may result in multi-organ involvement with significant morbidity and mortality.(26, 27) Hospital admission and the use of intravenous aciclovir are required.

Premature prelabour rupture of membranes

Primary infection

There is a lack of data regarding the management of preterm prelabour rupture of membranes in individuals with a primary HSV infection. Multidisciplinary discussion is required and the gestational stage needs to be taken into account. Treatment with intravenous aciclovir 10 mg/kg every 8 hours should be administered before delivery. Caesarean section is considered to be beneficial despite prolonged rupture of membranes, although the benefit of this approach might be reduced by prolonged contact with infected maternal secretions.(21) Corticosteroids are not contraindicated.(22)

Recurrent infection

One study showed that expectant management of 29 women with preterm premature rupture of membranes at <31 weeks’ gestation who had active recurrent genital herpes was not associated with neonatal transmission of HSV.(28) It was concluded that the risks of prematurity outweighed the risks of HSV transmission during a recurrent episode. The mean duration of membrane rupture was 13.2 days (range 1–35 days), 45% of infants were delivered by Caesarean section, and 8% of women had received antiviral therapy for control of symptoms.(28)

Prevention of HSV infection during pregnancy

At the first antenatal visit, all pregnant people should be asked whether they or their partner have had genital herpes. In one US study, 22% of the 3192 pregnant couples enrolled were at risk for HSV-1 or HSV-2 infection.(5) The only independent risk factor for HSV-1 infection was having a partner with oral herpes, and this accounted for 75% of incident HSV-1 infections. Of 125 women susceptible to HSV-2 infection, 14% acquired HSV-2 infection during pregnancy. Most newly acquired infections were subclinical. The risk of becoming infected with HSV was eight times greater in relationships of ≤1 versus >1 year.(5)

Although there are no clear evidence-based guidelines to support clinical decision-making for the management of pregnant people with a partner who has a history of herpes infection, the following actions are recommended on theoretical grounds (GRADE C):

- Female partners of men with genital herpes should avoid sex when lesions are present.

- Asymptomatic female partners of men with genital herpes should have serology testing to determine their HSV status.

- Consistent use of condoms throughout pregnancy may prevent the acquisition of HSV infection.

- Suppressive antiviral therapy for the male partner should be considered if the couple is discordant with respect to HSV-2 antibody status.

- Pregnant people should be advised about the risk of acquiring HSV-1 from oral-genital contact. Therefore, if a partner has oral herpes then oral sex should be avoided.

- Although routine serological screening in pregnancy has been recommended by some authors, universal screening is unlikely to be cost effective because of the high number needed to treat to prevent a single case of neonatal herpes.(29)

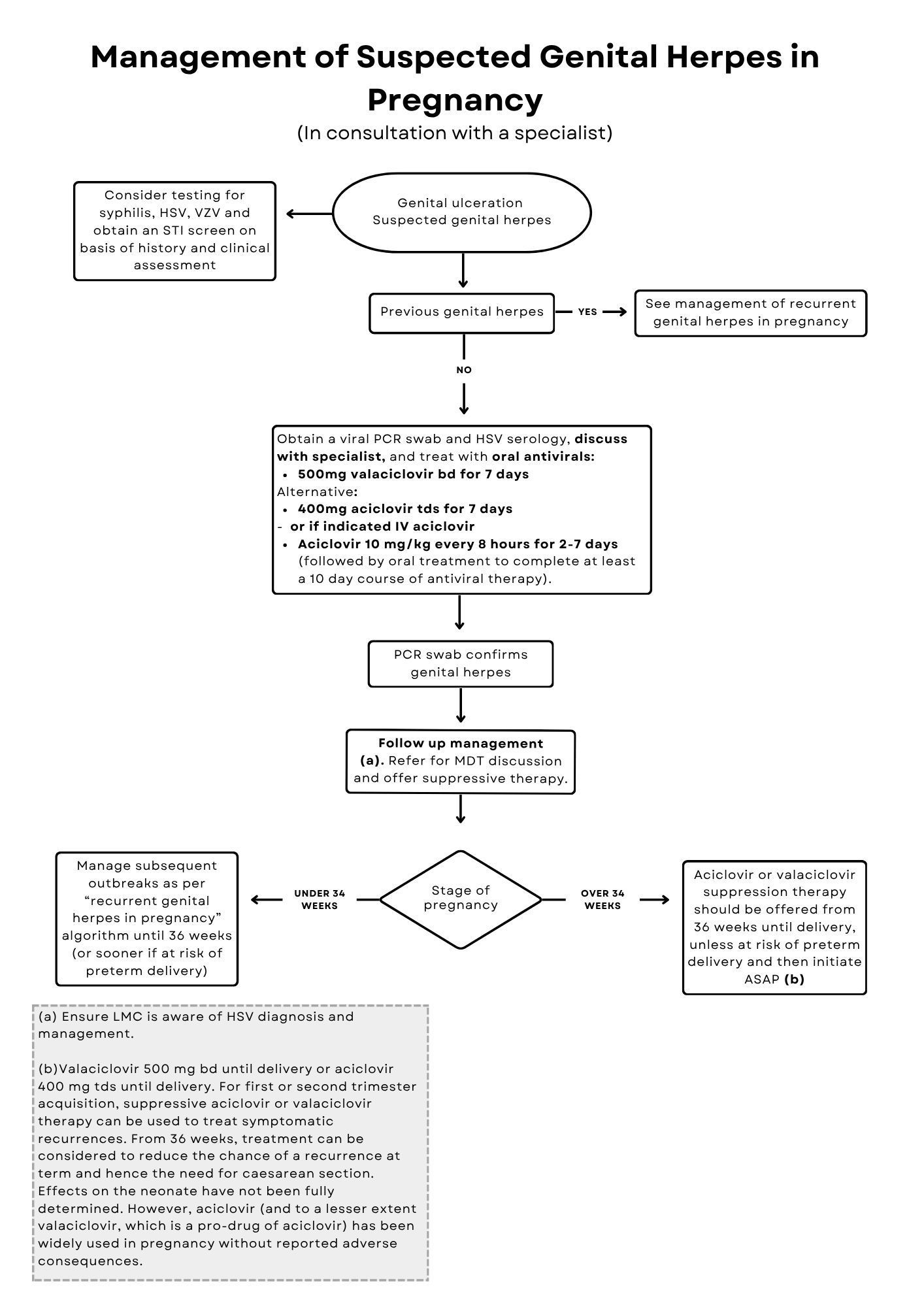

Management of genital herpes in pregnancy

Relevant treatment algorithms are shown in Figures 4, 5, and 6. The first clinical episode may not be due to a primary infection because previous infection may not have been recognised/diagnosed. PCR (genital swab) and HSV type specific IgG serological testing in conjunction with clinical evaluation will help to identify whether HSV in pregnancy is a primary infection. A primary first episode is determined by being seronegative for HSV-1 and HSV-2 in the blood but the PCR swab testing HSV positive. Testing results should be discussed with an expert who understands the sensitivity and specificity of available testing methods. For any HSV infection during pregnancy, it is important to note that no intervention is completely protective against maternal-fetal transmission. Therefore, all pregnant people with a history of genital herpes should be given information about neonatal surveillance. Pregnant people within 4 weeks postpartum who present with a first episode of genital herpes and/or disseminated HSV are likely to have been shedding at the time of delivery. They may have been unwell without classical herpetic lesions. In these situations, the baby should be considered at highest risk of neonatal HSV and managed accordingly.

First episode: first and second trimester acquisition

- Management should be based on each individual’s clinical condition, using standard dosage antiviral therapy for primary and recurrent episodes (see Use of antivirals in pregnancy and breastfeeding above for details). GRADE C

- The pregnancy should be managed expectantly and vaginal delivery can be offered.

- Prophylactic suppressive antivirals in the last 4 weeks of pregnancy (oral aciclovir 400 mg three times daily or oral valaciclovir 500 mg twice daily) reduces clinical recurrences, asymptomatic shedding, rate of caesarean section and virus in genital tract. Use must be balanced with risks of medication to newborn. Clinical trials underpowered to evaluate efficacy of preventing transmission to the newborn, and neonatal disease has been reported after maternal suppression.

First episode: third trimester acquisition

- Offer treatment with oral aciclovir or valaciclovir according to clinical condition, as for non-pregnant individuals (see First Clinical Episode of Genital Herpes chapter for details).

- Advise suppressive therapy with valaciclovir 500 mg twice daily or aciclovir 400 mg three times daily to reduce viral shedding and risk of recurrences.

- Delivery should be by Caesarean section, especially in people infected within the third trimester because of high asymptomatic HSV shedding rates and insufficient time between infection and delivery for a complete antibody response. GRADE B

- If vaginal delivery is unavoidable, consider treating with intravenous aciclovir and request urgent referral to a paediatrician experienced in HSV infection (see Neonatal HSV Infection chapter for more information). GRADE C

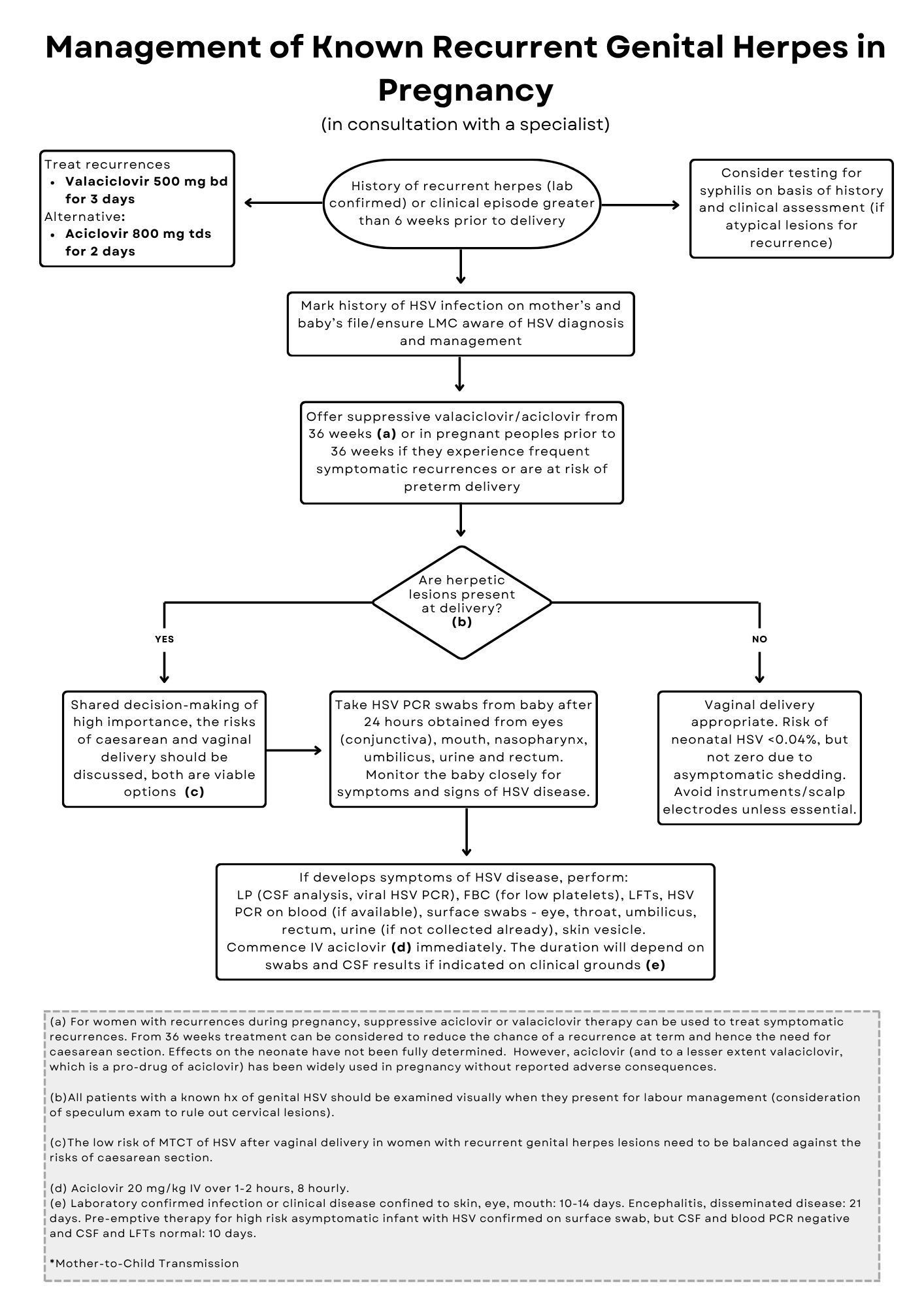

Recurrent genital herpes

- Document the presence of a history of genital herpes in clinical notes for both the pregnant person and the neonate.

- Symptomatic recurrences of genital herpes during pregnancy are usually brief, but can be treated with oral antivirals in the first or second trimester if troublesome.

- Sequential testing in the third trimester to predict viral shedding at delivery is not indicated.(30)

- Prophylactic treatment with valaciclovir 500 mg twice daily or aciclovir 400 mg three times daily from 36 weeks’ gestation (or earlier if at risk of preterm delivery) decreases the number of clinical recurrences and reduces the need for Caesarean section. GRADE B

- Vaginal delivery is appropriate if no lesions are present at delivery.(31)

- Caesarean section should not be performed in people who do not have lesions at delivery.(31) GRADE B

- In people who have recurrent genital lesions at onset of labour, it is common practice to deliver by Caesarean section because of the small risk of infection in the neonate. However, because the fetal risk is low, this must be balanced against the risks of Caesarean section and therefore genital lesions at the onset of labour are therefore regarded as a relative (rather than absolute) indication for Caesarean delivery.(31) GRADE C Ideally, this scenario should be discussed with the pregnant person by the primary caregiver early in pregnancy, in conjunction with specialist advice. It is important to remember that the risk of maternal-fetal transmission is higher with shedding of HSV-1 than with HSV-2.

- Caesarean section does not provide complete protection against maternal-fetal transmission of HSV.(32)

- In the context of vaginal delivery, scalp electrodes and instruments should not be used unless there is a clear indication because skin trauma may increase the risk of HSV transmission.

- Anecdotal evidence suggests that intrapartum intravenous aciclovir could be considered, but the value of this therapy has not been assessed in clinical trials.

- In those who present with a recurrent episode of HSV in late pregnancy, antiviral treatment will reduce the duration of symptoms and viral shedding. There are no studies documenting the duration of viral shedding in this situation, but it has been stated that vaginal delivery is safe if labour commences after 48 hours of treatment with antivirals.(33) This recommendation is consistent with the principles of episodic treatment.

References

- Brown ZA, Benedetti J, Ashley R, et al. Neonatal herpes simplex virus infection in relation to asymptomatic maternal infection at the time of labor. N Engl J Med 1991; 324 (18): 1247-52.

- Brown ZA, Wald A, Morrow RA, et al. Effect of serologic status and cesarean delivery on transmission rates of herpes simplex virus from mother to infant. JAMA 2003; 289 (2): 203-9.

- Looker KJ, Garnett GP, Schmid GP. An estimate of the global prevalence and incidence of herpes simplex virus type 2 infection. Bull World Health Organ 2008; 86 (10): 805-12, a.

- Baldwin S, Whitley RJ. Intrauterine herpes simplex virus infection. Teratology 1989; 39 (1): 1-10.

- Gardella C, Brown Z, Wald A, et al. Risk factors for herpes simplex virus transmission to pregnant women: a couples study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005; 193 (6): 1891-9.

- Eskild A, Jeansson S, Stray-Pedersen B, Jenum PA. Herpes simplex virus type-2 infection in pregnancy: no risk of fetal death: results from a nested case-control study within 35,940 women. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 2002; 109 (9): 1030-5.

- Li DK, Ferber JR, Odouli R, et al. PCORI Final Research Reports. Does Treating Genital Herpes during Pregnancy Improve Birth Outcomes? Washington (DC): Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Copyright © 2021. Kaiser Foundation Research Institute. All Rights Reserved.; 2021.

- Stone KM, Reiff-Eldridge R, White AD, et al. Pregnancy outcomes following systemic prenatal acyclovir exposure: Conclusions from the international acyclovir pregnancy registry, 1984-1999. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2004; 70 (4): 201-7.

- Pasternak B, Hviid A. Use of acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir in the first trimester of pregnancy and the risk of birth defects. JAMA 2010; 304 (8): 859-66.

- Brocklehurst P, Kinghorn G, Carney O, et al. A randomised placebo controlled trial of suppressive acyclovir in late pregnancy in women with recurrent genital herpes infection. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1998; 105 (3): 275-80.

- Scott LL, Sanchez PJ, Jackson GL, et al. Acyclovir suppression to prevent cesarean delivery after first-episode genital herpes. Obstet Gynecol 1996; 87 (1): 69-73.

- Wald A. Genital herpes. Clin Evid 2002: Jun (7): 1416-25.

- Watts DH, Brown ZA, Money D, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of acyclovir in late pregnancy for the reduction of herpes simplex virus shedding and cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003; 188 (3): 836-43.

- Ramsey P, Andrews W. Antiviral suppression to prevent recurrence of herpes simplex virus (HSV) infections in pregnancy: a meta analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003; 189 (6): S98.

- Sheffield JS, Hollier LM, Hill JB, et al. Acyclovir prophylaxis to prevent herpes simplex virus recurrence at delivery: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol 2003; 102 (6): 1396-403.

- Smith JR, Cowan FM, Munday P. The management of herpes simplex virus infection in pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1998; 105 (3): 255-60.

- Therapeutic Goods Association. Prescribing medicines in pregnancy database. The Australian categorisation system for prescribing medicines in pregnancy. Available at: https://www.tga.gov.au/products/medicines/find-information-about-medicine/prescribing-medicines-pregnancy-database#:~:text=Category%20B3,human%20fetus%20having%20been%20observed. Accessed 26 Mar 2024.

- Ahrens KA, Anderka MT, Feldkamp ML, et al. Antiherpetic medication use and the risk of gastroschisis: findings from the National Birth Defects Prevention Study, 1997-2007. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2013; 27 (4): 340-5.

- Sheffield JS, Fish DN, Hollier LM, et al. Acyclovir concentrations in human breast milk after valaciclovir administration. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002; 186 (1): 100-2.

- Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®) [Internet]. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; 2006-. Acyclovir. [Updated 2018 Oct 31]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501195/. Accessed 18 Jul 2024.

- Brown ZA, Gardella C, Wald A, et al. Genital herpes complicating pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2005; 106 (4): 845-56.

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Management of genital herpes in pregnancy (Oct 2014). Available at: https://www.rcog.org.uk/media/5t0nborx/management-genital-herpes.pdf. Accessed 13 Mar 2024.

- Brown EL, Gardella C, Malm G, et al. Effect of maternal herpes simplex virus (HSV) serostatus and HSV type on risk of neonatal herpes. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2007; 86 (5): 523-9.

- Poeran J, Wildschut H, Gaytant M, et al. The incidence of neonatal herpes in The Netherlands. J Clin Virol 2008; 42 (4): 321-5.

- Hemelaar SJ, Poeran J, Steegers EA, van der Meijden WI. Neonatal herpes infections in The Netherlands in the period 2006-2011. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2015; 28 (8): 905-9.

- Frederick DM, Bland D, Gollin Y. Fatal disseminated herpes simplex virus infection in a previously healthy pregnant woman. A case report. J Reprod Med 2002; 47 (7): 591-6.

- Thurman RH, König K, Watkins A, et al. Fulminant herpes simplex virus hepatic failure in pregnancy requiring liver transplantation. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2010; 50 (5): 492-4.

- Major CA, Towers CV, Lewis DF, Garite TJ. Expectant management of preterm premature rupture of membranes complicated by active recurrent genital herpes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003; 188 (6): 1551-4; discussion 4-5.

- Cleary KL, Paré E, Stamilio D, Macones GA. Type-specific screening for asymptomatic herpes infection in pregnancy: a decision analysis. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 2005; 112 (6): 731-6.

- Arvin AM, Hensleigh PA, Prober CG, et al. Failure of antepartum maternal cultures to predict the infant's risk of exposure to herpes simplex virus at delivery. N Engl J Med 1986; 315 (13): 796-800.

- Remington JS, Klein JO, Wilson CB, Baker CJ. Infectious diseases of the fetus and newborn infant. 6th ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2006.

- Kimberlin DW, Lin CY, Jacobs RF, et al. Natural history of neonatal herpes simplex virus infections in the acyclovir era. Pediatrics 2001; 108 (2): 223-9.

- Sauerbrei A, Wutzler P. Herpes simplex and varicella-zoster virus infections during pregnancy: current concepts of prevention, diagnosis and therapy. Part 2: Varicella-zoster virus infections. Med Microbiol Immunol 2007; 196 (2): 95-102.